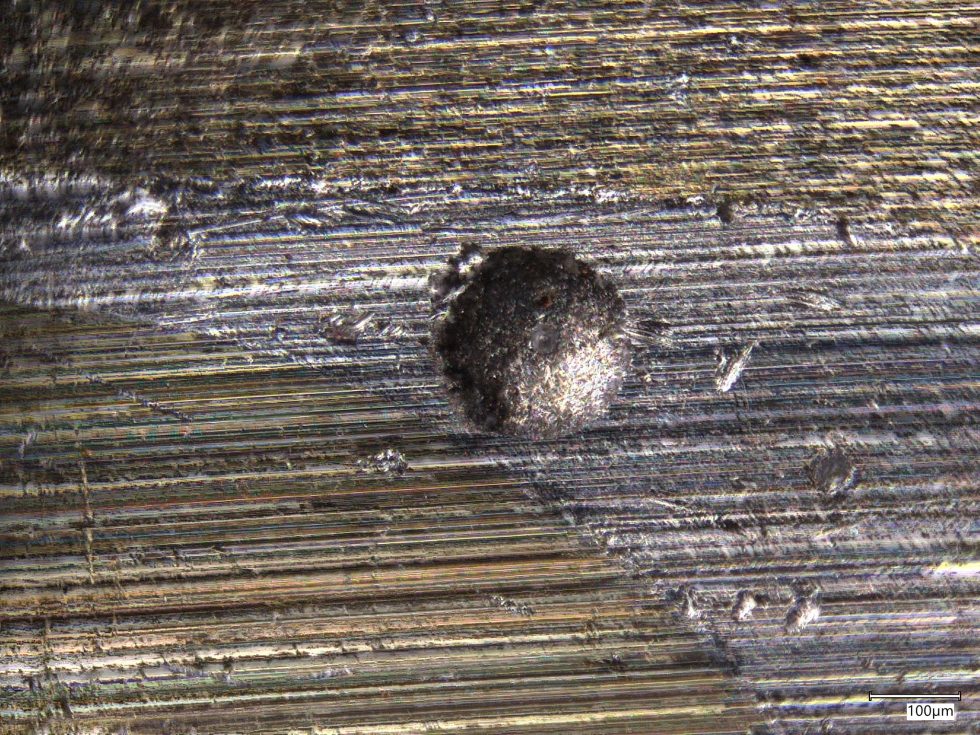

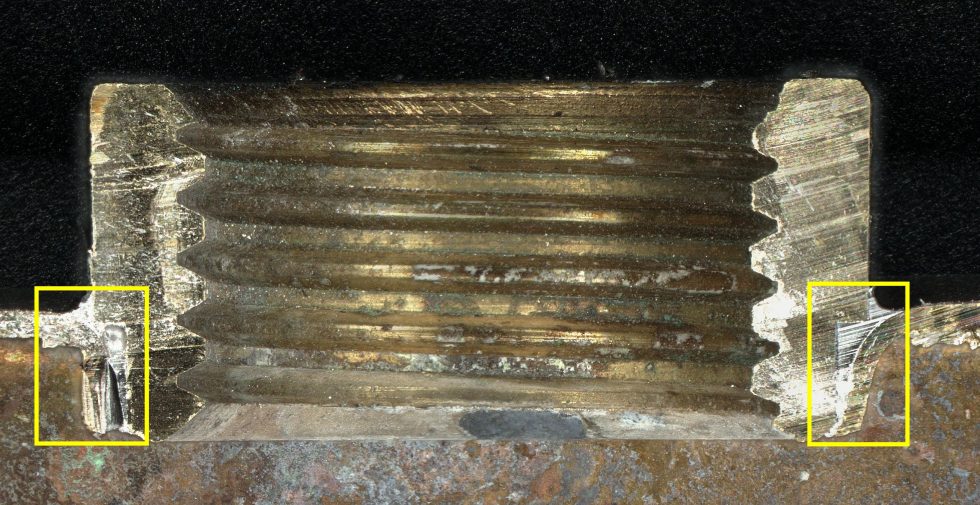

I’ve now reached part three and it’s time to briefly summarize the first two articles and, above all, to evaluate the reactions of the manufacturers, or rather their silence. As the case may be. Today’s test is about Radicooler (Qingdao YTeng Electronic Technology Co., Ltd.) and Magicool (Qingdao Magicool Electronic Technology Co., Ltd.) and their OEM products, which are also available in Germany, for example, from Amazon & Co. And I will also show that the original from Magicool fits perfectly, while you should better keep your hands off all the OEM clones and the stuff from Radicooler. And yes, it will also be about the annoying lead and shoddy workmanship such as air bubbles in tin and lead (picture below).

Today I’m testing four radiators again, two of which belong in the hazardous waste bin. Here is the tabular overview:

| Manufacturer | Model (size) |

| Radicooler (Qingdao YTeng Electronic Technology Co., Ltd.) | HRC360C 360 mm (AliExpress) |

| Magicool (Qingdao Magicool Electronic Technology Co., Ltd) | MC-RAD120G2 (Caseking) MC-RAD120G2 X-Flow (Caseking) |

| Richer-R (Magicool OEM product) |

120 mm Slim Radiator (Amazon) |

But first I will summarize a few important things from the first two parts:

Reaction of manufacturers and importers so far

Let’s start with the material used. Caseking has withdrawn the Dabel series from Barrow from sale until clarification with the manufacturer, but Barrow is obviously sitting this out comfortably. At Bykski, the distributor in Germany has reacted to some extent and Bykski has also issued a statement, but I am not satisfied with it. Watercool has made a public statement, but has not contacted me. Well, the case was clear in the end. EK also got in touch, but only after the very unsuccessful adaptation by Tom’s Hardware US to clarify the issue with the H90. Thermaltake consulted me in advance and we tested the Pacific series together, so that the information is now correct. I haven’t heard anything from Corsair yet either. However, there was no response at all to my inquiries about the flux residue in some radiators. Manufacturers such as EK and Bykski have remained completely silent in this regard, despite specific inquiries. Magicool will also be affected today, I can already spoil that for you

Brass or copper?

Of course, brass should not be demonized in general and copper exclusively praised as salutary when it comes to purely thermal issues. A little zinc creates more stability and also allows for thinner-walled ducts if this alloy is deliberately used to reduce the wall thickness and thus also the thermal resistance. Then, assuming good engineering, you can even get just below the values of copper in thicker walls. If you want to. Companies such as Hardware Labs have been successfully trying to reduce the size of structures for years, while others simply use brass to reduce costs. So the devil is always in the detail and in which path a company ultimately decides to take.

But as I already wrote in the first part: everyday performance is not the subject of this series of articles, but the pure material analyses and the detection of prohibited substances. I would also ask those who use these articles in their media to really pay attention to the nuances and not just break the content down into a short form using their own words, which may be misleading. In the case of lead, this is really clear and it must be criticized without reservation; in the case of brass, you always have to look at the overall concept. Perhaps I will adapt the introduction to the first article in this regard, because not everyone will read the original text. I am also planning another article that deals with the manufacturing process in detail.

In addition, if you don’t look at it with purely German eyes, you have to bear in mind the different meanings of copper and brass. Historically, in the English-speaking world, a distinction is actually only made between copper and aluminum radiators. Interestingly, the subtleties of the distinction between brass and copper are of no interest to anyone there, especially not to the marketing department. You have to keep this in mind when the respective PR department creates such websites and then translates them into German.

Where lead likes to hide

After talking to one of the major OEMs, I also expanded the areas that I examine. After all, soldering is not only done on the channels (tubing, fins) and in the pre-chamber (tank), but also on the threaded inserts for the fittings. I have also analyzed some of the newly added areas for the radiators already tested, but found nothing negative. That’s good! In order to remain more comparable and to shorten the explanation of the proportions, this time I generally measured everything in wt% (weight percent). I got the tip about the pre-chamber from the industry, because even the contract manufacturers have parts manufactured and supplied by third parties or even fourth parties.

Quality management is then hardly possible if a brand has the radiators of a model manufactured by different OEMs, who in turn use their own and very different suppliers. Only the final inspection can help. However, what is written in some certificates is pure waste, because everything has never really been fully checked. Or you do it like 80Plus.org, where there is a clean bill of health for all customers of a platform, without even being checked in detail.

Of course, the sense or nonsense of banning lead is open to debate, but if there are legal regulations, then they must be complied with unconditionally. And even if some people may not accept the purpose of such bans in individual cases, in the end it is and remains a question of fair competition. As a market participant, you have to bow to it. Whether or not you address this as a reviewer should be left to the respective tester. I think the topic is important and will continue to do so, as well as testing other components.

You can easily save up to 15% on soldering costs by using lead solder, and that’s not even including the time saved. And there are markets where nobody really cares about lead and where nobody takes a closer look anyway. If you want to switch to lead-free, you have to have around 10 tons of tin and more ready for a new soldering tank, cleaning and changing is difficult to impossible. So you have to rebuild and that is precisely why there are still many companies today that shy away from this effort. You can’t do both at the same time.

And that’s exactly why today it’s once again about the details and the credibility of the specifications (and therefore also of the supplier or manufacturer), whereby I can already spoil the fact that I have once again found huge amounts of lead where none belongs.

For reasons of convenience and also sustainability, because I have to cut the radiators open and thus render them unusable, I test the smallest ones that can be obtained quickly, i.e. usually the 120 models, as long as they are available. This is not a problem, because it is not the length that is decisive, but the material itself. After all, it’s not the cooling capacity that matters today, but the components. I’m going to do this and other tests because no one has ever done it in this depth and published it.

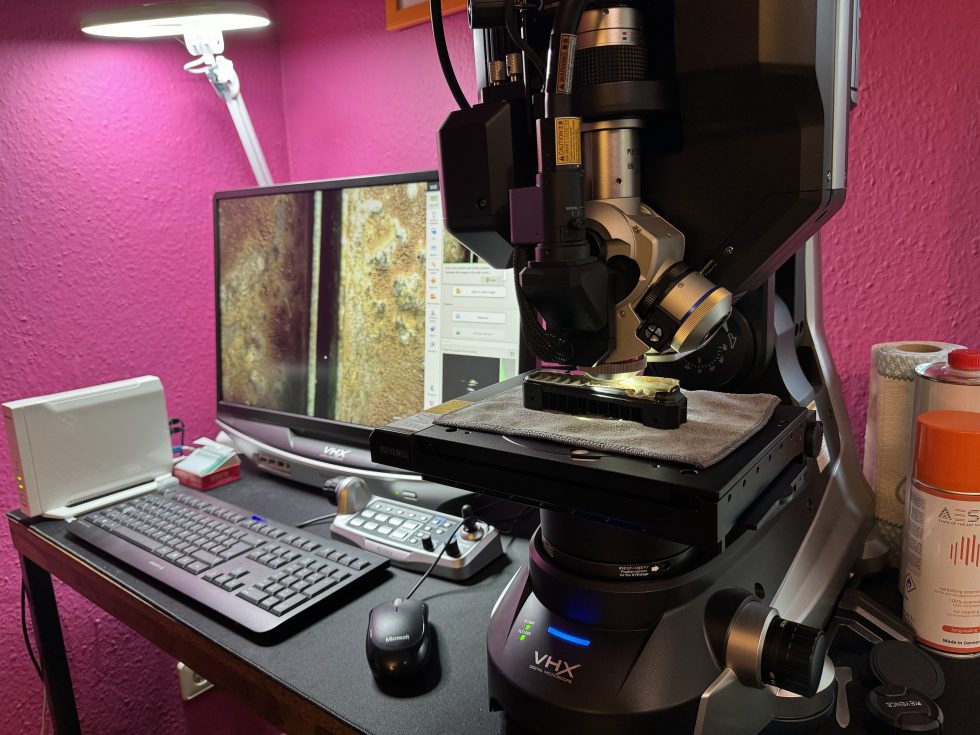

Test equipment for the material tests, accuracy and test preparation

My Keyence VHX 7000 and EA-300 are used for material testing and measuring the radiators, enabling both exact measurements and fairly precise mass determinations of the chemical elements. But how does it actually work? The laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) I used for the article is a type of atomic emission spectroscopy in which a pulsed laser is directed at a sample in order to vaporize a small part of it and thus generate a plasma.

The emitted radiation from this plasma is then analyzed to determine the elemental composition of the sample. LIBS has many advantages over other analytical techniques. Since only a tiny amount of the sample is needed for analysis, the damage to the sample is minimal. The real damage is caused in today’s article by my rather coarse cutting and separating tools. This still quite new laser technique generally requires no special preparation of the samples for material analysis. Even solids, liquids and gases can be analyzed directly.

LIBS can detect multiple elements simultaneously in a sample and can be used for a variety of samples, including biological, metallic, mineral and other materials. And you get true real-time analysis, which saves a tremendous amount of time. As LIBS generally requires no consumables or hazardous reagents, it is also a relatively safe technique that does not require a vacuum as with SEM EDX. As with any analytical technique, there are of course certain limitations and challenges with LIBS, but in many of my applications, especially where speed, versatility and minimally invasive sampling are an advantage, it offers significant benefits.

I would first like to point out that the results of the percentages in the overviews and tables were intentionally rounded to full percentages (wt%, i.e. percent by weight), as it happens often enough that production fluctuations can occur even within the presumably same material. Investigations in the parts-per-thousand range are nice, but today they are not useful when it comes to reliable evaluation and not trace elements. I therefore only deliberately searched for lead in the percentage range, although the RoHS even criticizes trace elements. I have provided more information on accuracy and methodology below as a link to a separate article.

However, every day in the lab starts with the same procedure, because when I start, I work through a checklist that I have drawn up. This takes up to 30 minutes each time, although I have to wait for the laser to warm up and the room to reach the right temperature anyway.

- Mechanical calibration of the X/Y table and the camera alignment (e.g. for stitching)

- White balance of the camera for all lighting fixtures used

- Check alignment of LIBS optics and standard lens, calibrate alignment of laser to own optics (x300)

- Test standard samples of the materials to be measured and correct the curve if necessary (see image above)

MagiCool Xflow Copper Radiator I (MC-RAD120G2X)

| Lagernd | 26,90 €*Stand: 27.04.24 12:38 |

| lagernd | 31,94 €*Stand: 27.04.24 10:50 |

| 4-6 Werktage | 33,48 €*Stand: 27.04.24 12:36 |

MagiCool 120 G2 Slim Radiator

| Lagernd | 32,90 €*Stand: 27.04.24 12:38 |

| lagernd | 39,18 €*Stand: 27.04.24 10:50 |

| Lager Lieferant: Sofort lieferbar, 2-4 Werktage | 39,78 €*Stand: 27.04.24 12:36 |

24 Antworten

Kommentar

Lade neue Kommentare

Urgestein

1

Urgestein

Urgestein

1

Urgestein

Urgestein

Mitglied

1

Urgestein

1

Urgestein

Veteran

Urgestein

Urgestein

1

Urgestein

Urgestein

Urgestein

Alle Kommentare lesen unter igor´sLAB Community →