Windows XP: Clear fronts due to lack of competition

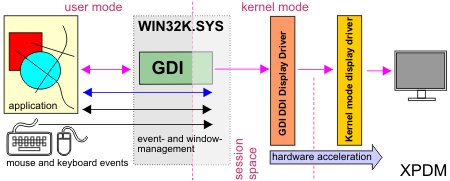

Up to and including Windows XP, the GDI plays the central role in the output of all 2D content,which can be seen in the (slightly simplified) schematic. Let’s now retrace the process by looking at the creation and output of a line. Our mouse movements for drawing a line are first sent as information to win32k.sys, the central point for all possible events. No matter if mouse or keyboard inputs or all graphical tasks, here information is collected and distributed purposefully. Our application now receives this information and converts it into a GDI drawing command. This ends up in the GDI and thus again in win32k.sys. Let’s just follow the purple arrows.

So under XP, the old 2D world is still fine. This simple scheme also shows why 2D hardare acceleration is quite easy to implement, provided of course that the graphics card used also has the corresponding capabilities. By the way, the blue arrow indicates the feedback to the program, so that it knows that window contents have changed (e.g. when another window no longer covers parts) and that the contents must be redrawn by the program.

Up to and including the Radeon HD1xxx series at ATI and the Geforce 7xxx at Nvidia, all consumer graphics cards also have a separate 2 unit. This was dropped by both manufacturers with the introduction of the DX10 cards with the unified shader architecture.

Vista: CPU instead of GPU – buffer instead of direct delivery

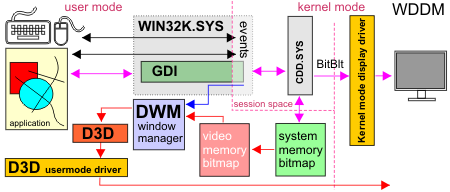

Under Windows Vista, a completely new path was taken, as already explained in the first part. To understand the whole thing better, we have to simplify it further. Up to the GDI, the drawing is analogous to XP, but the task of win32k.sys to manage the windows is now taken over by the DWM (Dynamic Window Manager). In addition, starting from Windows Vista the window management is done completely by Direct3D. The window of each application is therefore stored in the texture memory of the graphics card as a 3D texture. Actually a practical matter, but the GDI can no longer address this content directly. The communication chain therefore seems to be interrupted. This is where the already mentioned double buffering comes into play.

Memory waste and detours lead to the subjectively perceived sluggishness of Vista

What happens exactly? Let’s look at the red arrows. Instead of the actual graphics driver (under XP the DDI display driver), the new CDD (Canonical Display Driver) is addressed, which is a direct part of Vista, independent of the graphics card. While the final window content is already in the graphics card memory as a texture, an additional equivalent buffer must now be created in the system memory for each window (window width x window height x 4 bytes for the color). In the system memory buffer, the later window view is first created as a bitmap using the conventional method and only then transferred to the video memory as a texture as the final product. The DWM in turn manages the windows and creates the content via Direct3D. The DWM also receives the information when an area in a window has changed and thus needs to be redrawn (blue arrow). At this moment the DWM copies the contents of the system memory into the video memory and lets the window be re-rendered via Dirct3D (D3D). The program itself (in contrast to the solution under XP) does not have to draw the contents again.

We quickly notice that hardware acceleration is no longer possible with these detours and that direct drawing also loses considerable performance compared to XP. All of this then manifests itself in the familiar symptoms, on the basis of which Vista is quickly assumed to have a certain sluggishness and, above all, high memory requirements.

Windows 7: Hardware acceleration in homeopathic doses

We already mentioned that Windows 7 can support parts of the GDI commands via hardware acceleration again, as long as WDDM 1.1 drivers are used. If these are missing, as is the case with some older Intel graphics solutions, Windows 7 again behaves similar to Vista. What does this mean for us exactly? It is important that a double buffer does not necessarily have to be created for every window anymore. The so-called “non local memory” (also called “aperture space”) takes the place of the system memory. This is a certain area of the normal system memory that can also be accessed directly by the graphics card. If a window area now changes by moving or fading in, the content of this area is simply copied into the video memory of the graphics card without detours.

Compared to XP, however, only a few GDI commands can hope for GPU support: Render Text, ColorFill, BitBlt with the default ROPS, AlphaBlend, TransparentBlt and StretchBlt. In short, for non-insiders: rendering text, solid fill with simple colors, copying image content and transparencies. While drawing geometric figures is not supported at all, copying image contents and filling can even be passed directly past the “aperture space” and output directly.

Interim conclusion

Windows 7 reduces memory requirements by eliminating double buffering. Even Vista benefits from the new driver model in retrospect. Hardware acceleration has been possible again since the platform update (which also introduced DirectX11), similar to Windows 7. The disadvantage, however, is the complexity and the possible driver problems. We were on the trail of these again.

- 1 - Einführung: Die Relevanz der 2D-Grafikausgabe über das GDI

- 2 - Das 2D-GDI und dessen Grafikausgabe von XP bis Windows 7 im Detail

- 3 - 2D-Grafikausgabe über das GDI: direkt oder gepuffert?

- 4 - Die Symptome der HD 5xxx-Serie und deren Relevanz unter Windows 7

- 5 - Tom2D: Unser einfacher 2D-GDI-Benchmark

- 6 - Tom2D: Textausgabe

- 7 - Tom2D: Linien

- 8 - Tom2D: Kurven

- 9 - Tom2D: Polygone

- 10 - Tom2D: Rechtecke

- 11 - Tom2D: Ellipsen

- 12 - Tom2D: Blitting

- 13 - Tom2D: Stretching

- 14 - Fazit

16 Antworten

Kommentar

Lade neue Kommentare

Mitglied

Veteran

Urgestein

1

Urgestein

1

Urgestein

Urgestein

Urgestein

Urgestein

Mitglied

Urgestein

1

Urgestein

Mitglied

1

Alle Kommentare lesen unter igor´sLAB Community →