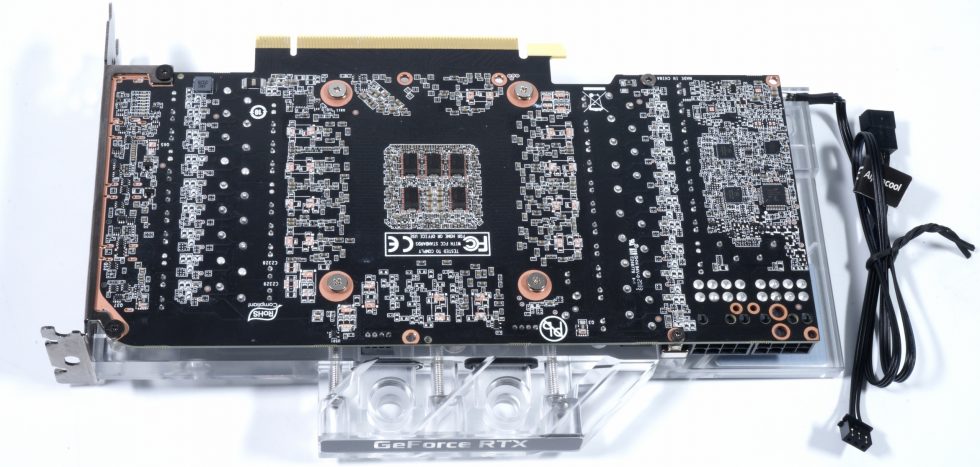

We know the situation that the GDDR6X memory on NVIDIA’s GeForce RTX 3080 is a real heater and one always lives in fear that too high temperatures might cause long-term damage. On the other hand, there are of course plenty of thermal pads on the market as a possible replacement, some of which promise true miracles and are correspondingly expensive. But how does one actually want to check such pads?

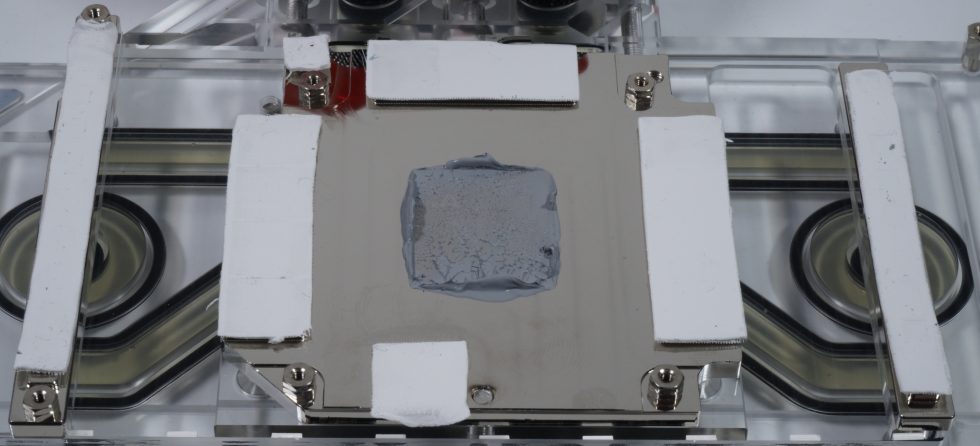

As a starting point, I use the exact pads that NVIDIA uses on the original GeForce RTX 3080 FE. I was able to trace the path of these soft and crumbly pads back to the manufacturer at the time, and I also use them for my tests as a comparative value in the lowest power class. Because if we’re being honest, it’s really not high-end, but it’s designed for durability and the softest consistency possible without silicone bleeding out here like so many ultra-soft pads.

Four performance classes : Which pads do we choose as a reference?

The intention behind the test is a division into four performance classes, because it should be logical that a pad (100 x 100 x 1 mm) for less than 20 euros does not come close to one for 100 euros in the same size. However, the intermediate levels between the two extremes are also very interesting here, because often a little less equals significantly cheaper and is usually still completely sufficient for the intended purpose.

| Performance class | Thermal conductivity | Test pattern |

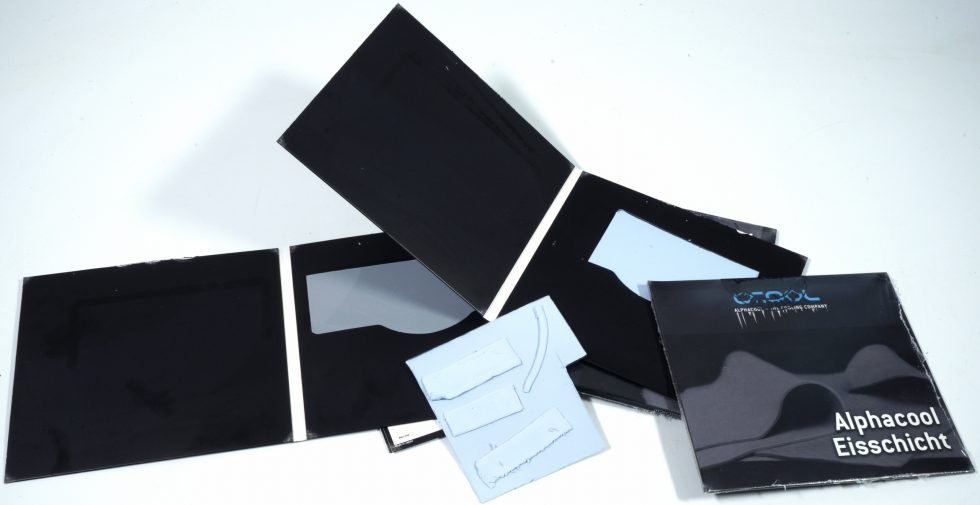

| Entry level | < 5 W/(m*K) | Alphacool Eisschicht Ultra Soft 3 W/(m*K) |

| Middle Class | 5 to 8 W/(m*K) | Alphacool Rise Ultra Soft 7 W/(m*K) |

| Upper class | 9 to 12 W/(m*K) | Alphacool Apex 11 W/(m*K) |

| High-End | > 12 W/(m*K) | Alphacool Apex 14 W/(m*K) |

Exactly at this point Alphacool comes into play, who include exactly such 1 mm pads with a thermal conductivity of 3 W/(m*K) on the GPX coolers as a bonus. The advantage of such ultra-soft pads has been described often enough, because especially on the current large Ampere graphics cards with the very different height packages, it is important to establish good contact to the surfaces that need to be cooled without a lot of back pressure, without the nasty silicone can leak out later. Then the pads also become hard and clearly lose performance. You can’t use it like that.

In addition, the new pad with 7 W/(m*K) as a replacement, which will replace the white pads at Alphacool in the foreseeable future, is added to the test portfolio for the pads as an advancement to the next higher class. Both are also available separately in the shop as Alphacool Eisschicht and Rise. But that alone is no reason for an article, even if the improvement to the pad with 7 W/(m*K) would actually have been worth a test. I round up today’s test for the reference values with two more pads: once 11 W/(m*K) and once 14 W/(m*K).

I know the source for these pads as well, they are both originally from Japan this time and they hold up to what was printed on them. But a pad test needs to be well thought out in order to exclude all eventualities and to keep the measurement tolerances as small as possible. That’s why I didn’t skimp on the effort and went a little further out on a limb. At this point, my explicit thanks also go to Alphacool, who offered themselves as a reference in this case and also made the pads available for pre-tests without obligation or influence. I needed pads whose specifications I could believe, if I were to start a comparative series. Because the higher the data on thermal conductivity, the more healthy distrust you should have.

With the cheaper pads nobody has to cheat, but everything from 5 W/(m*K) becomes also fast times the miracle bag, also concerning the price. Then various Chinese OEMs are already in Pinocchio land, supplying various resellers and labels, with massive overpricing right out of the box. But more on that later. In fact, there are also good examples with useful data. A big Japanese Player sells such extreme pads, which can only be purchased through resellers, but not directly as an end customer. Unless you buy a whole pallet right away. This was another reason to take advantage of Alphacool’s offer, as the two higher-end pads come exactly from this Japanese manufacturer. And they are then unfortunately already a little more expensive.

I will generally use pads with a thickness of 1 mm for the tests, as they not only fit ideally to the water block, but are also more informative in the test than much thinner pads, where the differences can drift in the direction of measurement tolerance. Thicker always works, of course, but thinner would mean an enormous amount of extra work for an identical statement. So it remains with the 1 mm pads, the rest can derive everyone itself, since the real thermal resistance rises or falls proportionally to the thickness of the pads. Ergo: the thicker the required pad has to be, the more its thermal conductivity matters. Simple physics, then.

By the way, in the picture at the top we see such a bluish and very crumbly pad with already used stripes as a backing, which as a block with 100 x 100 x 1 mm already costs a little over 100 Euro and from the consistency rather reminds of highly viscous thermal paste. I wonder if it really justifies the high price Please turn the page and be amazed further back!

Bisher keine Kommentare

Kommentar

Lade neue Kommentare

Artikel-Butler

Alle Kommentare lesen unter igor´sLAB Community →